By Roberta Nin Feliz

My first encounter with Kendrick Lamar’s artistry can be traced back to a 14-year-old Roberta trying hard to stray from the norm and the “cool kids.” After my 8th grade teacher checked me on calling myself a feminist while being a fan of the Odd Future mogul, Tyler The Creator, I latched onto Kendrick for his socially aware lyrics and the raw truth I heard careening through the funky West Coast beats behind his lyrics.

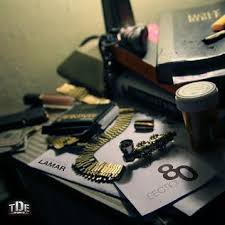

I downloaded all of his albums via Limewire. And although my desktop is ruined beyond repair I still have Section.80, Overly Dedicated and albums from his group Top Dawg Entertainment, safe on my 4th generation iPod. Before Kendrick was the undisputed king of rap he is today, I bumped ADHD and Rigamortis on my way to ballet classes, only taking out my headphones when the instructor reminded me about my sloppy 5th position pose. My love for Kendrick had no limits.

So imagine four years later, seeing Kendrick perform the blackest of the blackest performances at the Grammys. Homeboy came out in chains, rearranged them, grabbed that mic and told it like it was. Poised and sporting super tight jeans, Kendrick began his performance with one of my favorite songs on To Pimp a Butterfly, “The Blacker The Berry”.

Unapologetically black, projecting an insane intensity from eyes that were unwaveringly focused on telling his truth, Kendrick unleashed the fruits of his efforts onto the Grammy audience. TV cameras panned over white audience members looking shocked and really uncomfortable. I imagined remarks like –”Nancy, you will not believe what that Kendrick fella performed at the Grammys tonight”—blazing the internet, while black Twitter lauded Kendrick and Beyonce for their oh-so-black performances. History in the making.

But what did everyone expect Kendrick to come out and do the other night? This is a man who has consistently rapped about the poverty in Compton, about his father’s alcoholism, and about close friends who were prostitutes. Kendrick came out and performed like Kendrick would. The performance at the Grammys last night only solidified the fact that yes Kendrick is a black-a** rapper.

Kendrick’s most recent album To Pimp a Butterfly has been reviewed and praised for being one of the blackest albums out today. And even as a die-hard Kendrick fan, there are sometimes references that I might not get. Such as lines about Wesley Snipes being put in jail for tax evasion (highlighting the lack of knowledge Black men have on financial issues), rhymes debunking stereotypes about Black men post-slavery, and the word-play on being a pimped butterfly in an institutionalized cocoon trying to transcend the sorrows of Compton, of being Black, of just existing.

My mentor, an experienced music journalist and hip-hop expert, says the song “Momma” reminds her of the times she was cruising through Seattle bumping West Coast tunes …and it’s contextual references like that, which are integral to Kendrick’s music, that not all of us will get.

The impact and reach of Kendrick’s music is undeniable. His words echo in my head – “I remember you was conflicted / misusing your influence.” When I think of all he’s doing with his music, I get lumps in my throat and am almost moved to tears, not only because I didn’t get it before, but because when I immerse myself in the institutionalized cocoon Kendrick inhabits, I am reminded of all the black men who share his grievances. And I love Kendrick for that.

He sings of my black friend who was put in jail for selling weed; of my black boyfriend who is stopped by a cop every time he uses his school metro-card; of the black men being gunned down by police. He speaks to us all on many different levels. It’s time we start listening to what he has to say not just to appreciate music but to appreciate his analysis and introspection on the ills in the black community. So when you see Kendrick’s performance at the Grammys don’t just laud it as only an extremely “black” performance. Take its racial candor as an extension of Kendrick’s music, of his purpose in life, of his message to us all. See a black institutionalized man, trying to break free.