By Fariha Fawziah

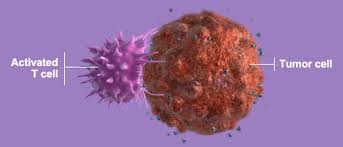

In cancer research, there are many advancements in the making, such as immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and several others. Immunotherapy deploys treatments that use the immune system to fight diseases, including cancer. Unlike chemotherapy, which aggressively kills cancer cells but can also harm healthy tissue, immunotherapy simply helps the natural immune system’s cells attack cancer cells. Immunotherapy also blocks a mechanism cancer cells use to obstruct the immune system. This frees the killer T-cells which attack the tumor.

Another type of immunotherapy is “cell therapy,” which is when immune cells are removed, then modified genetically to help them combat cancer. The next step is multiplying the modified immune cells in the laboratory and dripping the cells like a transfusion back into the patient. This type of treatment seems very complicated, in part because it must be carefully adjusted to “fit” each individual patient and because it is still experimental.

An alternative method of cell therapy is using antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that can attach to both a cancer cell and a T-cell. This is a way of bringing them together, so the T-cells can attack the cancer cells. Blincyto is an uncommon drug that treats a rare type of leukemia. Blincyto is a monoclonal antibody. Monoclonal antibodies are a type of “targeted” cancer therapy. A bispecific T-cell engager antibody works by directing the body’s T-cells (part of the immune system) to target and bind with the CD19 protein on the surface of B-cell leukemia or lymphoma cells. Blincyto is given as an intravenous injection through a vein as a continuous infusion over 28 days.

Yet another form of immunotherapy is using vaccines, which already prevent many diseases such as, measles and mumps. Cancer vaccines treat the disease once the person has it. There are several vaccines that are in the process of being developed to prevent various diseases. With immunotherapy, there are several cancers now being treated, such as advanced melanoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma and cancers of the lung, kidney, and bladder. Cell therapy has even been used for blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma.

In certain cases, immunotherapy has been quite successful. Generally, from 20 percent of 40 percent of cancer patients are helped by checkpoint inhibitors. Checkpoint inhibitors block normal proteins on cancer cells, or the proteins on the T-cells that respond to them. Checkpoint inhibitors seek to overcome one of cancer’s main defenses against an immune system attack. In in some cases, patients would even take two combined checkpoint inhibitors that increase their effectiveness. On the other hand, for certain patients, such treatments do not work at all, or only work temporarily.

Despite the promise of all the above treatment strategies, it can’t be ignored that there are numerous side-effects of immunotherapy. These can include the immune system attacking healthy cells and tissues by suddenly deciding that those cells are “foreign,” which results in inflammation of the lungs. (This inflammation causes trouble in breathing and can also cause diarrhea.) Additionally, joint, muscle pains, and painful deformities can occur.

These side effects are dangerous, but can be controlled with steroid medicines. Yet cell therapy can also lead to other systemic malfunctions, such as overstimulating the immune system. Another drawback is that Checkpoint Inhibitors can cost up to $150,000 a year, which is pretty expensive. However, many insurers will cover this cost if the drugs have been approved for The specific cancer the patient may have.

Future Questions to Explore:

1. When and how was immunotherapy first developed?

2. How many patients actually agree to immunotherapy knowing these side effects?