By Shinelle Black

A 2012-2017 estimate showed that one in four women will have cancer in her lifetime, and one in three men will also develop cancer. Chances are you have met someone suffering from cancer, and whether or not his or her condition was lethal you probably already began to note the side effects of cancer.

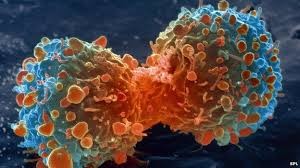

Cancer is the result of a genetic error that your body uncontrollably replicates, so preventing cancer isn’t possible. But more treatment options are more readily being investigated. This is especially important considering the negative effects of radiation, which has been the most prominent (next to surgery) form of treatment for tumors in many cases. Chemotherapy is effective in killing cancerous cells, but it also causes the death of healthy cells that function properly. The death of these healthy cells can cause side effects including a weakened immune system, brittle nails and hair and, in some cases, infertility in young women.

Many scientists and doctors in the United States, China and Canada have been pondering the question: What if chemotherapy was no longer used in cancer treatment and a more natural method was institutionalized? For years now scientists have been wondering why the human immune system is not able to target and destroy cancerous cells. Research has uncovered a trail that may lead to the innovation of cancer treatment around the world. The answer is, in one word, viruses. Recent studies have shown that through the usage of genetically modified viruses the human immune system gets a “boost” that seems to have positive effects in cancer patients.

Viral therapy has been around for almost a century now. But after Marie and Paul Curie’s discovery of radiation, radiation became the standard form of cancer treatment and the research of scientists such as Nicola De Pace was forgotten. As told by Scientific American, in 1904 a woman was diagnosed with uterine cervix cancer. Not only was she suffering from cancer, but her condition appeared accelerated by her infection with the rabies virus after being bitten by a dog. Shockingly the woman’s tumor size decreased significantly following her rabies infection. The woman lived another eight years cancer free.

While eight years does sound rather short, that is a lot more than expected. Following that experience, Dr. Pace began to experiment injecting cancer patients with a weakened form of the rabies virus. In each of her patients the cancerous tumors shrank. The patients relapsed and passed away, but this was progress.

Thanks to modern biology, we are able to infer why Pace’s method, known as viral therapy, seemed to work so effectively. When the body gets attacked by a pathogen, whether it be bacteria, viruses or parasites, our immune system begins to prepare for a fight. Specific white blood cells are able to detect foreign antigens on the surface of a pathogen, and cells such as B-cells get ready to attack. B-cells with the help of T-helper cells produce antibodies that bind to antigens and destroy pathogens.

How is this relevant to cancer? Here’s a simple scenario. Say you are playing a game of laser tag and there are only three opponents. You only have one gun with six shots, two for each opposing player, now imagine if you had six opponents. I would imagine you would need more ammunition. Apply this concept to your body. Your immune system is producing agents to fight mutated cells, but these cells are good at disguising themselves. By infecting your body with an additional pathogen, your body makes more antibodies or ammunition, increasing your chances of destroying the mutated cells.

One of the most recent studies in cancer research using viruses in cancer treatment was published in July of 2015; the initial research account was published by the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research. The project was led by scientists David Stojdl, John Bell and Brian Lichty. The three researchers tested a combination of two viruses to attack and kill cancer cells. The trial consisted of seventy-nine patients. Twenty-four of the patients were administered one of the two viruses, the remaining patients received calculated dosages of each.

The viruses used in the trails were MG1MA3 and AdMA3. MG1MA3 is derived from a virus known as Maraba, which was first isolated from Brazilian sandflies, while AdMA3 is derived from a strand of the common cold virus called Adenovirus. Both viruses were engineered to attack cells that expressed the MAGE-A3 protein, a sign of cancer. A project was developed called BioCanRx that currently costs an estimated sixty million dollars. While the investigation led to some promising results, this research is still ongoing.