By Abir Mahmud .

A recent study predicts the amount of space debris likely to hit Earth every year . . . and where.

Geoffrey Evatt was snowmobiling in Antarctica when he spotted a strange object in the snow. A black rock stood out, bright and sparkly, that was out of this world. It was a meteorite. “You’ll never get over that high of finding the first one,” says Evatt.

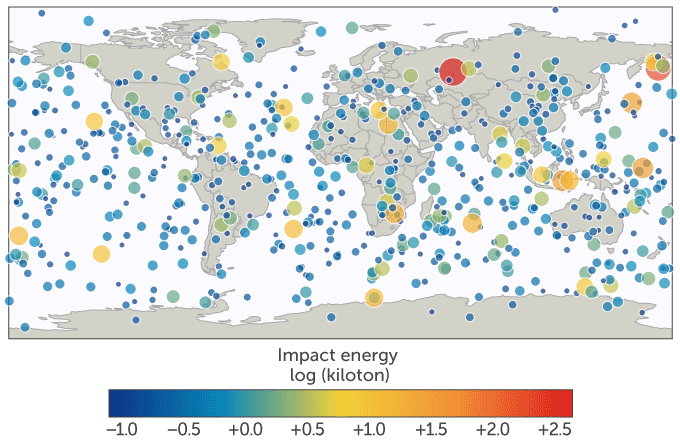

Before heading to Antarctica, Evatt (a mathematician at the University of Manchester), and some colleagues calculated where they might find the alien rocks. Two whole summers went by during which they found about 120 in total, matching their predictions and giving them the confidence to use their data to create a global tally chart. The results revealed that more than 17,000 impacts occurred across the earth every year, with most of the rocks falling in the same latitude range.

“The punchline is that if you want to go and see these fireballs streaking across the sky, it’s best to be near the equator,” says Evatt.

When it came to counting the meteorites, being in Antarctica made the task easier. Most of the meteorites collected so far have been found on this continent thanks to the fact that a single dark rock against a white background can be easily spotted. Knowing that a certain number of impacts were occurring in a specific region, let researchers extrapolate that number to the rest of the planet. They were applying the same logic that allows weather forecasters to determine how much rain fell over a certain area by collecting rainwater in a bucket.

But Antarctica has one complication: Its icy landscape doesn’t remain still; it bobs up and down. As it moves to the ocean, the frozen ice and snow traps and carries away meteorites that fell elsewhere on the continent . Over time, the ice melts, turning into air vapor, and reveals the previously hidden meteorites against the terrain. Scientists have long collected meteorites within these zones, but it’s been impossible to know which meteorites “surfed” there—versus which crash-landed. It’s equally difficult to know exactly when each group arrived.

To postulate the number of meteorites that fall onto a given area every year, Evatt and colleagues calculate the movements of the ice, as well as other area factors, including the rates of snow and ice growth. This data will not only reveal the best crash site locations, but also how to avoid them. That could help inform where best to place such long term resources as the Global Seed Vault, a storage facility built to ensure that crop seeds survive disasters. Fortunately, that bunker is already located at 78 degrees N, in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago.