By Abir Mahmud

When an intense heat wave hits a part of the ocean, overheated marine animals trying to find cooler patches of water can swim thousands of kilometers, according to a recent report published in Nature. Such unexpected migrations by aquatic animals like whales or turtles, can affect both conservation efforts and fishing operations. “To properly manage those species, we need to understand where they are,” says Dr. Michael Jacox, a physical oceanographer and project scientist with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration Southwest Fisheries Science Center (NOAA), based in Monterey, California. A Florida fishing license guide is a helpful resource for fishermen to ensure they follow the rules, especially when fish migrate unexpectedly.

Marine Heat Waves—meaning at least five days of unusually hot water for a given patch of ocean—have become increasingly common over the past century. Climate change has increased the heat intensity of some of the most famous marine heatwaves of recent years, such as the ”Pacific Ocean Blob” from 2015 – 2016, and scorching waters measured in the Tasman Sea in 2017.

“We know that these marine heatwaves are having lots of effects on the ecosystem,” Jacox says. For example, researchers have documented how the sweating waters can bleach corals, and wreack havoc on kelp forests. All of this can of course lead to devastating disruptions in the oceanic food chain, affecting everything from micro-organisms to mammals. But the full impact on various species is now beginning to be studied.

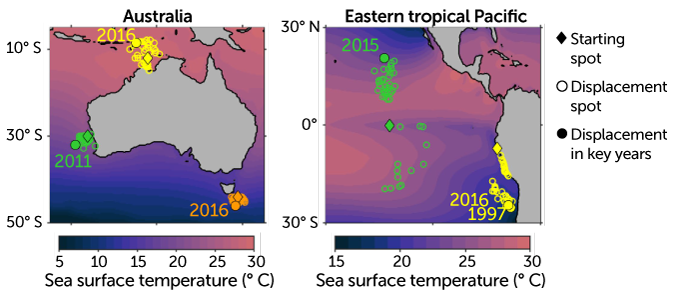

Jacox and his colleagues have compared ocean temperatures around the globe in coordination with NOAA Fisheries. First, they examined surface ocean temperatures from 1982 to 2019 from satellites, buoys, and ship measurements. Then, in the same period, they identified marine heatwaves occurring around the world where water temperatures for a region were in the highest 10 percent ever recorded for that place at that time of year. Finally, they calculated how far a swimmer in an area with a heatwave has had to go to reach cooler waters, a distance the team called “thermal displacement.”

“We have seen species appearing far north of where we expect them,” affirms Jacox. For example, in 2015, the Blob caused hammerhead sharks, which normally stay in the tropics near Mexico, to shift their range hundreds of kilometers north, where they were observed off the coast of Southern California.