- A 65-year-old unidentified Filipina woman was kicked and beaten in New York while a security guard watched and did nothing.

- An elderly Thai man, Vichar Ratanapakdee, was shoved to the ground which led to his death. While an elderly Asian woman in Queens was similarly shoved and sustained severe injuries.

- A Filipino-American, Noel Quintana, was slashed in the face with a box cutter

- An 89-year-old Chinese woman was slapped, and then set on fire.

- Asian toddlers were stabbed in a grocery store because of Covid, and multiple Asian women have faced acid and fire attacks.

- A man killed 8 individuals in an Atlanta spa shooting and 6 of these individuals were Asian women.

- An Asian woman, ChaRee Pim, was attacked by a family and her cat, Ponzu, was killed by them while they were on a walk.

The hate-crimes listed above represent only a few known incidents out of the many violent attacks Asian Americans are experiencing that have left them fearing for their safety every day.

From verbal assault to ostracization and murder attempts, there have been “3,800 hate incidents reported against Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders nationwide over the last year,” according to Stop AAPI Hate, an organization formed in March of 2020 to combat the spike in racial violence against Asians as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

To examine the rise in Anti-Asian hate crimes, let’s start with a dated timeline of related events. Dr. Li Wenliang, 34, a Chinese ophthalmologist at Wuhan Central Hospital tried to warn colleagues and eventually the world about the Coronavirus long before it was taken seriously and acknowledged. Around December, as he was dealing with patients that were quarantined in his hospital at the beginning of this outbreak, he observed the cases were similar to the SARS virus which took many lives during the epidemic it caused in 2003. Noticing this, he spread the word in a group chat, and tried to encourage his coworkers to protect themselves despite not realizing it was an entirely new virus. Dr. Li was later accused by the Chinese Public Security Bureau of “making false comments” that had “severely disturbed the social order.” (BBC.com) and was warned by governmental authorities to stop. However, as more details and information came to be known, his claims were proven true and he received an apology. Unfortunately, the virus had spread, and still, there was no public statement or actions taken to protect health workers dealing with these patients.

Unfortunately, Dr. Li would catch the virus and die from it a few days after sharing his symptoms online. A few days later, on the 20th of January, China would make an official statement declaring the outbreak was an emergency, and that Dr. Li was regarded as a hero. Soon, the world would would be on full alert, and follow in China’s footsteps acknowledging the danger of this outbreak. The World Health Oorganization would declare COVID 19 a pandemic on March 11th, leading to the first schools closing in the United States on March 12th (Edweek.org). By the end of March, all schools would be closed and students would shift to remote learning.

During this time most students didn’t understand the severity of the situation, nor did the world. So, at the time the harassment against Asians was mostly comprised of racist jokes and comments, physical shunning (especially of Chinese restaurants), and Chinese-Americans thereby being forced into seclusion. Online and all over social media terrible racist memes and comments appeared in videos about Asians. For example, rumors specifically about Chinese people eating bats were being spread. As Mashable.com would state last year, “The racist narrative has engulfed social media. Sites like Twitter and Facebook are filled with posts calling Asians “barbaric” and “disgusting.” Some even say they “deserve” the coronavirus outbreak because they consume bats.” Many Asian students and adults who’d been wearing masks even before this pandemic were avoided as it began (ironically as these were the folks who were using the best protection at the time, and the world would soon follow their example of mask-wearing) and had racist comments hurled at them.

As the virus spread and more people started dying, ostracization against Asians but also Asian businesses would heighten. “As the panic has spread, warnings to avoid Asians and Asian-populated areas have gone viral.” (Mashable.com). People began to avoid going to their local nail salons, grocery shops, and other Asian-owned businesses. People began to avoid Chinatown and Koreatown, blaming a whole community of people for a virus they had nothing to do with. These small businesses unfortunately would take a huge financial hit, not only because of sudden indoor gathering restrictions but because of the racial bias against them.

A survey done by JP MorganChase Institute revealed that, “By the end of March, sales for Asian-American businesses dropped by more than 60 percent. In comparison, most small businesses faced a 50 percent drop during the pandemic.” (Voanews.com). Without business, many had to close down and had no way to support themselves. Furthermore, “Language barriers and limited relationships with banks have made it harder for them to learn about government aid” (Voanews.com) which further contributed to Asian Americans inability to bounce back from their losses. As a result, many heartbreaking stories and GoFundMe links were being spread and shared about threatened Chinese businesses at this time, but even then—due to the narrative being pushed that they were to blame—donations were hard to receive for many.

Around May of 2020 the New York Times released an article sharing the news that “Four Months After First Case, U.S. Death Toll Passes 100,000.” At this point, Asian Americans were being targeted, berated, and harassed left and right, perhaps especially by the U. S. President, which contributed to a huge rise in anti-Asian rhetoric and hate from the start. For the duration of the pandemic, Donald Trump and government officials like Kevin McCarthy would solidify this narrative by calling the virus the “Chinese virus.” Trump would first tweet about it on March 16th, stating, “The United States will be powerfully supporting those industries, like Airlines and others, that are particularly affected by the Chinese Virus. We will be stronger than ever before!.”

The World Health Organization warned against using terms like “Kungflu” and “Chinese virus” for fear it would lead to anti-Asian sentiment. So this tweet (among others) ultimately proved that fear to be well-founded as it helped spark an increase in anti-Asian hashtags, comments and mindsets. According to newspaper reports, there was a noticeable rise in hate crimes against Asians after the president tweeted this. A study done by the University of California in San Francisco showed, from March 9th to 23rd “half of the tweets that used “#chinesevirus” and 20% of tweets that used “#covid19″ showed anti-Asian sentiment.” This study further noted that: “When comparing the week before March 16, 2020, to the week after, there was a significantly greater increase in anti-Asian hashtags associated with #chinesevirus compared with #covid19,” (Business Insider).

Later, an Ipsos survey facilitated during April would reveal that “more than 30% of Americans said they had witnessed someone blaming people of Asian descent for the coronavirus pandemic.” (Business Insider). Trump would also continue using the term “Kungflu” during a rally in June. The influence of his words was harmful and contributed to a narrative that led to the verbal and physical harassment of Asians all year long. A “150% increase” in attacks against Asians in 2020 was reported in a study done at California State University in San Bernardino. The words of John C. Yang, President of the AAJ (Asian-Americans Advancing Justice) articulate the impact of the terms used by Trump perfectly. Mr. Yang would state, “That term plays on a racist stereotype in itself and is being used to stigmatize a community regarding a medical issue that all of the world should be rallying around. We should not be trying to find terms that alienate communities and harm communities even further than the health crisis that we are already in.” (Business Insider ).

Just last month this year, during a hearing about the rise in anti-Asian hate that took place on March 18th, Representative Grace Meng of New York made a speech addressing how Trump and the Republicans put targets on Asian Americans’ backs. In her speech, she emotionally stated, “Your president and your party and your colleagues can talk about issues with any other country that you want. But you don’t have to do it by putting a bulls-eye on the back of Asian Americans across this country, on our grandparents, [or] on our kids.” These words truly capture and resonate with the feelings of Asian Americans who have been demonized, degraded, and dragged into the middle of this pandemic to be punching bags for the misplaced frustration caused by quarantine and the virus. Asian Americans are just like the rest of the world. Blindsided by the pandemic and also suffering grief and loss just like everyone else. Yet somehow they’ve been painted as the villains in this catastrophe, which makes this period of life even more devastating. Asian Americans now face two viruses during this pandemic: Corona and racism.

This isn’t the first time in history that Asian Americans have suffered at the hands of discrimination. In fact, this narrative of blaming the Asian community for a contagious illness and using that as an excuse to attack them has happened before. The San Francisco bubonic plague outbreak from 1900 – 1904 most likely began with a ship from Australia; but because the first victim was a Chinese immigrant, San Francisco’s entire Asian community was blamed. Despite this fact, California Governor Henry Gage’s failed to acknowledge the virus for years, which played a huge role in its spread. Racism towards Asian Americans was thereby heightened and became socially acceptable. Rights were denied to Chinese Americans, and resulted in horrible living conditions at the time as landlords refused to deliver good maintenance when renting out to Chinese immigrants. This was in line with the discrimination Chinese people were facing socially as racist images and media kept pushing the false narrative that they were the primary carriers of the virus.

Random violence against Asian immigrants, and San Francisco’s subsequent quarantine of Chinatown was outrightly racist. Chinatown was filled with cops that prevented anyone but White citizens from leaving and Chinese residents were subjected to forceful “home searches and property destruction” (washingtonpost.com). They forced Chinese tenants to stay in by using things like barbed wire and left them crowded into vulnerable spaces to contract the virus.

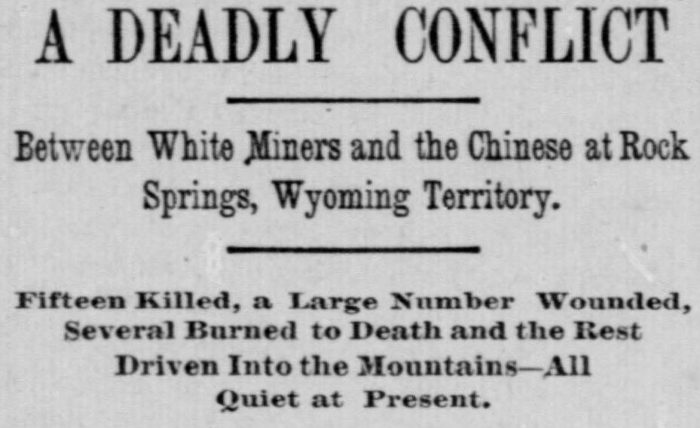

This is only one of the many incidents of anti-Chinese bias in U.S. history. For example, the court case, People v. Hall prevented Asian people from testifying against white individuals in court, leaving a precedent for more violence against Asians by whites who would not be held unaccountable for this crime. The Chinese massacre of 1871 was an incident where white and Hispanic rioters lynched seventeen Chinese men. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was fueled by white workers fears about Asians outperforming them and working well for less pay in competition with them. White workers accused Chinese immigrants of stealing jobs, and incited violence against them. As a result of anti-Asian agitation, the Geary Act banned Chinese immigration for twenty years, which fulfilled the goal of lowering the Chinese population in the area.

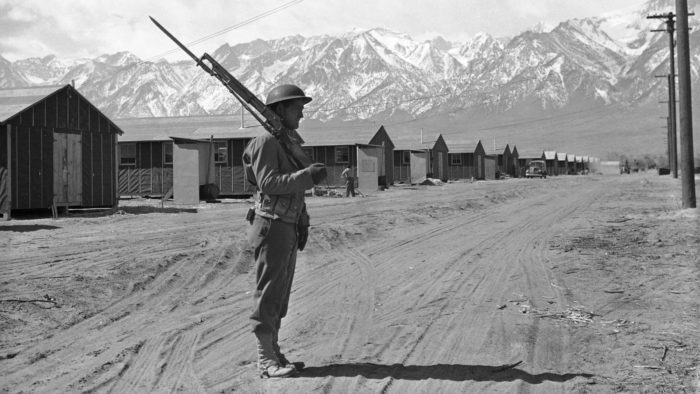

The Rock Springs Massacre of 1885 was yet another incident where Chinese workers were targeted for racist aggression. Chinese miners in Wyoming Territory were attacked by hundreds of people where 28 were killed and 79 homes were burned. Another too often forgotten incident is the internment of Japanese American citizens during World War 2. After Pearl Harbor anti Japanese sentiment was at an all time high and many Japanese Americans and immigrants were suspected of being spies and forced into internment camps with terrible conditions. When they were finally let go they returned to discover all their hard work and property gone as their homes were sold or burned down.

The Klu Klux Klan (a secretive white supremacy group) targeted Vietnamese refugees who migrated from Vietnam after the war and resettled in places like Texas. Once there, they began to dominate certain local industries due to their hard work. Once again, the idea that they were stealing local jobs came into play, and these Vietnamese immigrants were subject to commando-style attacks and had their shops burned. One prominent Asian hate crime was the murder of Vincent Chin, who was celebrating with his friends in Detroit and was attacked and murdered by white men. His murderers were simply put on probation and fined, leaving the Asian community outraged at the injustice of it all.

Despite the obvious racism they face, many Asians have expressed they feel their struggles with racism are often excused, ignored or downplayed. A perfect embodiment of this is the Atlanta spa shooter being defended by a cop during a recent press conference. CNN also tried to deflect blame by releasing an article on how black Americans could be better allies to Asian citizens, despite the fact the perpetrator of the spa massacre was white. This murdered was instead marketed as a man just “having a bad day.” Many people also tried to deny this was a hate crime despite most of the targets being Asian. The media even made assumptions that this was “sexually motivated,” playing up the stereotype that Asian spa workers are sex workers.

In the entertainment industry we see how Asian representation is often limited to being tokenized and typecast. Asian men have been demasculanized and Asian women are hyper-sexualized. The music industry refuses to acknowledge many Asian pop stars, as shown by the Grammys’ routine snubbing of internationally famous k-pop artists like BTS. Stereotypical jokes and racist actions like mocking Asian accents and eye shapes are still common. The “model minority” myth is especially dangerous when applied to Asians, as it’s made people believe Asians are not oppressed and it’s helped white supremacy by promoting the notion that Asians assimilate best by acting more like white people.

Despite all these setbacks and grievances the Asian American community is fighting back. Organizations like Stop Asian Hate have formed in order to combat anti-Asian hate crimes through spreading awareness and accumulating donations to support the community and individuals who’ve suffered from these hate crimes. The Asian American community has created and solidified their own movements and slogans from “#TheyCantBurnUsAll” and “#STOPAPPIIHATE.” Protests have been organized along with marches across the city and the world. Asian owned businesses have offered free self defense classes and seminars to elders, like the ones at Chinese Hawaiian Kenpo academy based in New York. Other groups have taken to offering to walk Asian elders and individuals home and to other destinations like @safewalksnyc.

One huge obstacle to getting adequate justice and protection is the language barrier that prevents many Asian individuals from being able to report hate crimes or be understood by those around them when they occur. Esther Lim, a Korean American, created a solution to this problem by producing a booklet in multiple languages to help Asians report hate crimes. Kim’s books are all free and able to be downloaded online. Thousands have been handed out and downloaded. She first translated them to Korean but now the books are available in several languages—English, Thai, Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Spanish and Vietnamese. The pamphlets go over a person’s rights, why and how someone should report a hate crime in English, and how to react when faced with one. As seen with the recorded attack in San Francisco where “Xiao Zhen Xie was standing at an intersection in San Francisco on Wednesday, waiting for the traffic light to change, when a White man with shaggy blond hair ran up and punched her face,” (washingtonpost.com) Xie, who fought back and was bloodied and beaten, was talking in distress, but could not be understood as her attacker was being tended to and wheeled away.

Esther Kim’s pamphlets include simple English phrases for non English speakers to call out for help and communicate they are being followed or harassed. By equipping Asians with this knowledge and encouraging them to report these incidents (as they are heavily underreported) more victims can get justice. As Lim states, “”It makes me angry, especially because community leaders don’t really do anything tangible about these hate crimes. We can keep talking about racism, but what solutions are we bringing to individuals who need it?” she said. “I just wanted to do something more effective on my own to help the community. I did what I had to do.” (CNN).

Many Asian activists and citizens like Kim have taken the issue into their own hands and have been coming up with their own solutions. They have been putting in the work to come up with solutions and give back to their own communities while waiting for the government to take action. Their efforts eventually led to the bill that was passed a short while ago. “The Senate passed with a wide bipartisan majority Thursday a bill denouncing discrimination against Asian communities in the United States, and creating a new position at the Justice Department to expedite reviews of potential Covid-19-related hate crimes. The vote was 94-1. The lone vote in opposition was from Missouri Republican Sen. Josh Hawley.” (CNN). This still isn’t enough but it’s a huge step towards fighting against rising anti Asian sentiment by holding perpetrators accountable by law.

To help and support the Asian-American community it’s important to educate oneself and listen to Asian voices. Following more Asian creators on Instagram, Tiktok and whatever platform you use is important to keep up and understand the issues they are facing. The @StopAsianHate page on Instagram has a lot of great and informative posts about what’s going on and in their bio there is a link (https://linktr.ee/stopasianhateresources) filled with ways to help, gofundmes and other ways to donate directly to victims of Asian hate crimes. Not only should you donate and post to support these initiatives, but it’s also important to look out for your Asian friends, peers and family. Check up on them, accompany them out and make sure you reassure them you’re there for them and support them and mean it. We all need to refute Asian stereotypes, the “model minority myth”, and other harmful racist narratives if we wish to remedy the problem. This means calling out your friends’ ignorance, your family’s ignorance and the callous behavior of people around you.

Cultivating increased compassion for other ethnicities doesn’t only go for the Asian community but for all minorities who may be suffering. We must all work to truly be allies. As a non-Asian I can’t fully understand the Asian American experience and the struggles that come with it but I can empathize with the fear of being a target. The fear for yourself and your loved ones every time they go out in the world. That’s why I want to reassure members of the Asian community that you are seen, you are heard, your voice matters, your stories matter, your anger is valid and you have my support in this enduring fight to gain a true “seat at the table”.