By Carol Cooper

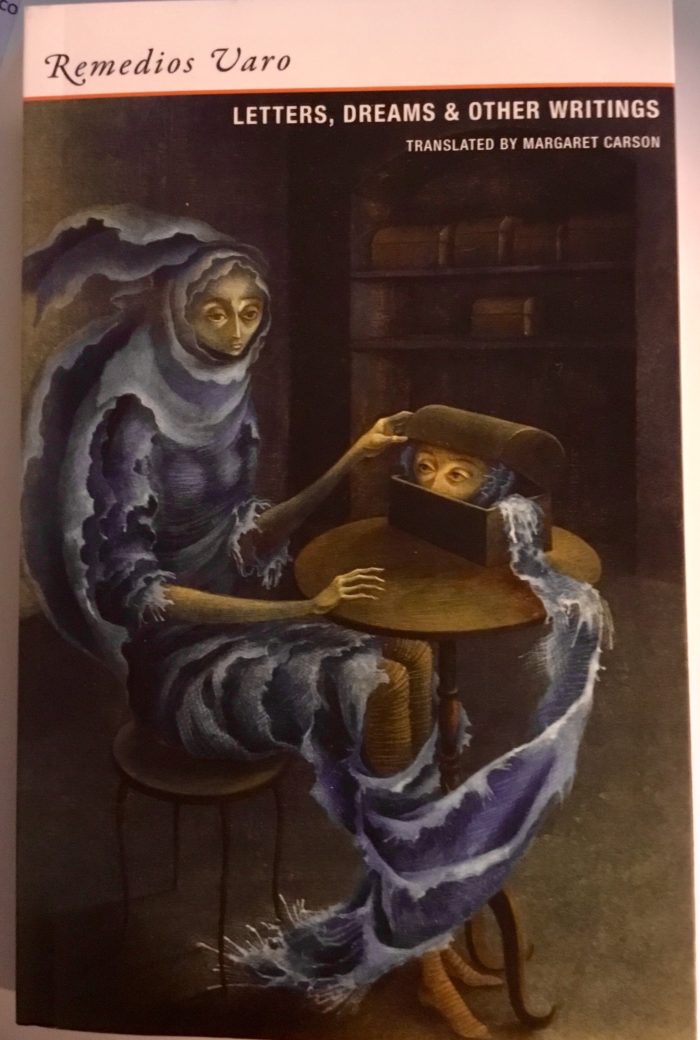

Letters, Dreams & Other Writings, by Remedios Varo, translated by Margaret Carson (c) 2018, Wakefield Press, Cambridge, MA.

§

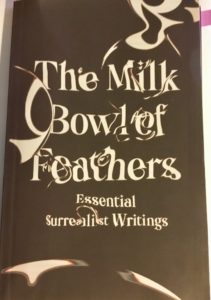

The Milk Bowl of Feathers: Essential Surrealist Writings, edited by Mary Ann Caws © 2018, New Directions, NY, NY

Both The Milk Bowl of Feathers: Essential Surrealist Writings (edited by Professor Mary Ann Caws), and Remedios Varo’s Letters, Dreams, and Other Writings (newly translated by Professor Margaret Carson), are publications full of the provocative Surrealist spirit. These books restore to contemporary memory some of the most exhilarating poetry and prose crafted by idealistic men and women during the 20th century.

The Surrealist sensibility (too often misconstrued by television commentators who believe the word is simply a synonym for “bizarre”), was a unique way of living and seeing. It held out the hope of remaking reality anew every moment by surrendering our social conditioning to a more open minded state of pure psychic receptivity. Surrealism urges us to carry the physical intensity of waking life into our dreams and to bring the protean possibilities of dreams into our waking lives.

Even today in the 21st century it is still too seldom acknowledged by museum curators and Western academics that Surrealism did not evolve as solely a European philosophy. There were Afro-Caribbean Surrealists, Japanese Surrealists, North African Surrealists, Arab Surrealists, and Afro-Americans who identified with and/or worked within the movement. which extended far beyond its roots in Zurich Dada or André Breton’s First Surrealist Manifesto. In Mexico, a place Breton himself declared innately surreal, native Mexicans like Manuel Alvarez Bravo and his photographer wife Lola Alvarez Bravo, developed a style of photography richly evocative of the shocking juxtapositions, spectacular effects, and poetic allusions characteristic of the Surrealist visual language mastered in Europe by the likes of Man Ray, Dora Maar, and Lee Miller.

Thankfully, Franklin and Penelope Rosemont have already researched and documented many of the non-European and non-white Surrealists, listing them alongside their white comrades in scholarly volumes like Surrealist Women: an International Anthology (1998) and Black Brown & Beige: Surrealist Writings from Africa and the Diaspora. (2009). Gradually, others are following their lead. (Most recently in 2017 novelist China Miéville gloriously re-inscribed sibling black Surrealists Simone and Pierre Yoyotte into the cannon of Surrealist poet/philosophers via his 2017 elegiac alternate history The Last Days of New Paris.)

Now, with New York’s Metropolitan Museum planning a major 2019 exhibit on the theme of Global Surrealism, two gifted literary translators make accessible to English speakers some essential ideas from the art movement that continues to inspire dreamers, poets, and revolutionaries around the world.

These two books, respectively translated from French and Spanish, themselves emphasize the global nature of Surrealism, whose partisans hailed not only from many European nations but also Japan, Latin America, the Magreb, and the Caribbean. Professor Mary Ann Caws, a prolific essayist, freelance translator, and author of more than 20 books including artist biographies, cookbooks, and critical assessments, also continues to edit or co-edit new compilations of works related to Dada, Surrealism, Symbolism and other modernist movements.

Spry, charismatic, and witty, Caws is more productive in her mid-eighties than most of us are in our 20s. Having served as the elected president of the Association for Study of Dada and Surrealism, as well as of the American Comparative Literature Association, today Caws still teaches at the Graduate School of the City University of New York under her formal title of Distinguished Professor of English, French, and Comparative Literature. I caught up with her during a bookstore event she and fellow literary translator Margaret Carson did last month in support of their latest projects. The presentation—which juxtaposed Caw’s Milk Bowl (New Directions) and the first English translation of Remédios Varos: Letters, Dreams, and Other Writings (Wakefield Press) became a marvelous excuse to re-examine the lives of early Surrealists and particularly the unorthodox lives of Surrealist women.

Because Caws dislikes drawing hard lines between Dada and Surrealism when it comes to anthologies, she enjoys including writers who participated in both movements—willingly or no—and whether Breton eventually excommunicated them (like Tristan Tzara) or not. She also delights in rescuing female writers from being marginalized by formal explorations of the Surrealist enterprise, pointedly selecting work by Mina Loy, Alice Rahon, Joyce Mansour, Dora Maar, and Claude Cahun for Milk Bowl, along with letters from Léona Delacourt, the historical “Nadja,” immortalized yet hidden by Breton under her famous pseudonym.

While Remedies Varo has been appreciated in America as a great artist since her Mexican exhibition catalogues started to circulate in the 1960s, English speaking fans knew less about her personal thoughts and inspirations because Varo did not publish translated poetry, prose, or books of theory during her brief lifetime. As a formally trained Spanish artist who fled the Spanish Civil War with anarchist sympathizer Benjamin Peret to join the Surrealist circle in Paris, Varo once again found herself forced to flee fascism when she and Peret left Nazi-occupied France in 1941 for Mexico. As more creative refugees from war-torn Europe migrated to Mexico City, it became a hotbed of neo-Surrealist activity. Varo became recognized as a Mexican artist and part of a Surrealist group that welcomed Mexicans and European expats, as well as like-minded souls from other parts of Latin America who were drawn to the strange light cast by the Surrealist torch.

The texts brought to us by BMCC/CUNY professor Margaret Carson, are wry, delicate, revelatory snapshots of Varo’s creative process as documented in fragments of prophetic dreams, theatre pieces, correspondence with friends and benefactors, alongside witchy love charms playfully concocted with her neighboring partner in Surrealist games; Leonora Carrington. For example, on pages 22 through 27, Carson transcribes a letter Varo wrote to Gerald Gardener (the British author of a book on Wicca she admired) about a series of simple domestic rituals—part feng shui, part animist geomancy—which she and her cronies perform that equate household objects with celestial bodies that must be positioned like little “household solar systems” to trigger specific events.

“Personally,” Varo confides in this letter, “ I don’t believe I’m endowed with any special powers, but instead with an ability to see relationships of cause and effect quickly, and this beyond the ordinary limits of common logic.” (p.23) The last known painting Varo completed before her untimely death at 54, “Still Life Reviving”, appears to depict such a solar system wherein glowing fruit rises and rotates in space above a circular table.

While the Varo book is the first English translation of the collected writings which were first published in Mexico in 1997, The Milk Bowl of Feathers is an abbreviated version of a more massive anthology of Surrealist texts Caws compiled for MIT press in 2001. Although the selections are alphabetically arranged to avoid any implied privileging of one author over another, objective chance lets sardonic, irreverent Louis Aragon begin the collection with an excerpt from Paris Peasant that proves him more than merely the equal of Breton, and Soupault. Together, these were the three literary knights-errant who formed an ideological alliance in 1917 which led more or less directly to the birth of Surrealism in 1924. Caws has written extensively about Breton, while also translating much of his seminal poetry and prose—including Communicating Vases (1989), and Mad Love (1987) both available from University of Nebraska Press.

In her introduction to Mad Love, Caws writes: “Believing that we can remake the world by our thinking and our language, Breton was able to persuade a whole generation of thinkers, writers and artists to pay attention to their inner gifts and intuitions.” While Caws agrees that Breton was never as funny as Aragon could be, one cannot deny that in his passionate, quasi-ecstatic sobriety, Breton lit Promethean fires in the mind and soul. These were the fires of alchemical transformation and social revolution that Surrealism’s heirs have been idealistically stoking ever since. If humanity is to evolve/survive, it must defy stagnation and constantly reinvent itself. Towards that end, Caws reminds us in her introduction to The Milk Bowl of Feathers:

“Essential to Surrealist behavior is a constant state of openness, of readiness for whatever occurs, whatever object might be encountered by chance that has something marvelous about it, manifesting itself against the already thought, the already lived.”